Yet again, today has been lost to all the work I should have been doing, but instead I spent the day tied to the fantastic website for the Old Bailey: http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/

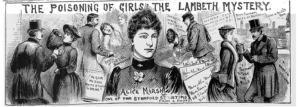

Luckily, one of my chapters focuses on exploring the music halls as a site of crime so I get to play around and explore the Old B on a daily basis. The crimes of one individual deserve a wider audience and so, I give you, the Lambeth Poisoner; Dr Thomas Neill.

In 1892, four years after the horrors of the Whitechapel murders by Jack the Ripper, Dr Thomas Neill was convicted of the murder of Matilda Clover. It was part of a case known in the press as ‘The Lambeth Poisoning Mysteries’ and centred around the strychnine poisonings for four prostitutes who had taken lodgings in Stamford Street, near to Gatti’s Music Hall on the Westminster Bridge road. The murder of Clover, which lead to Neill’s eventual conviction, was the only one that could be weel and truly linked to him and it is possible that Neill’s crimes would have gone undetected if he had not been overcome with greed and used them to try and blackmail worthy members of society.

In early 1892, a suspicious letter arrived on the desk of William Henry Broadbent, M.D. It claimed that a private individual had evidence that Broadbent had been hired to poison Clover (whose death had previously been recorded as due to alcoholic tremors) with strychnine pills and it would require a payment of £2,500 to stop them from taking this information to the police. Dr Broadbent, not a man to take blackmail lightly, took the letter to the police immediately and this opened a new investigation into the death of Clover.

Embarrassingly for the police it was revealed a somewhat shady corner of how death amongst the lower classes in London was treated. The original cause of death had been recorded as due to alcoholic tremors, as Clover had been receiving regular treatment for alcoholism for a Dr Robert Graham. He was unable to attend when Clover’s symptoms, violent stomach pain and convulsions, first began, recommending instead a Dr McCarthy from a near by practice. Unbeknownst to him, Dr McCarthy was also unavailable and sent in his place, his unqualified assistant, Francis Coppin. Taking her history of alcoholism into account and having no medical qualifications, Coppin later reported to Dr Graham that she had been suffering from excessive drink and that had been the cause of her death. Dr Graham wrote out the death certificate without seeing the body or talking to any of the other witnesses to her death, and Clover was chalked up to just another gin-addled tragedy. That Clover had been approached by a man in a music hall who she had invited back to her rooms, and had willingly taken some pills he gave her only to die shortly afterwards, was of no consequence to anyone. It was not until the letter that a second post mortem examination which showed traces of strychnine in Clovers stomach and other organs that a murder case was opened and three other cases in the area were re-examined, leading to Neill’s conviction.

When the Police finally caught up with Neill he attempted to implicate another lodger where he had been staying, Walter J. Harper, a medical student at St. Thomas’s Hospital. He claimed that Harper was responsible for the murders of at least five women, including Clover, known as the ‘Stamford Street Girls’, to whom, he claimed, Harper was well known as a supplier of illegal abortions, and that they had attempted to blackmail him for this very reason.

Although the cases were known as the ‘Lambeth Poisonings’ Neill did not restrict his activities to one area of London, evidence was also heard that he had poisoned a prostitute, Loo Harvey within a West End Music Hall and that he claimed she had died between the Royal Music Hall and the Oxford Music Hall. But in a stunning turn of events she was later revealed to be alive and gave evidence at his trial. It must have been a shock to Neill when Loo arrived in the witness box, as he had been convinced of her death and had attempted to use it in another blackmailing scheme. She claimed to have ‘pretended to have taken the pills’ he had given her, which turned out to be a pretty lucky escape.

The reason why these women all accepted drugs from a man they did not know was never questioned at the trial, but says something about the state of society at the time. Prostitutes were invariable down on their luck and suffering from numerous vernal diseases and addictions for which they would have been unable to get medical help. Neill used this to manipulate and kill them, just so that he could uses their deaths for blackmail, and it is unsurprising that the courts found that only one sentence could fit the crime, death.

But unlike his predecessor, Jack the Ripper, Dr Neill’s status as an early serial killer is confined to footnote in history. Maybe this was one monster that the public was able to reveal as just a man, and with his death, there was nothing to fear anymore.